Address

Arusha Njiro

Work Hours

80 Hours A week

Address

Arusha Njiro

Work Hours

80 Hours A week

Researcher: Eng Israel Ngowi

This study interrogates the 2024 Certificate of Secondary Education Examination (CSEE) results to quantify differences in academic achievement between private and government secondary schools in mainland Tanzania. A cleaned national file covering 5 363 centres across 31 regions was analysed with descriptive statistics and cross-tabulations. Private schools recorded a markedly lower mean GPA ( μ = 3.01) than their government counterparts ( μ = 3.82), indicating superior examination scores. Only 0.22 % of government schools attained the NECTA Grade A (Excellent) benchmark compared with 5.13 % of private schools. Regionally, Dar es Salaam and Pwani dominated Grade A counts, while Arusha fielded the highest-ranked government centre (Ilboru). The findings confirm earlier qualitative claims that the Fee-Free Basic Education Policy has strained public capacity (Lucumay & Matete, 2024), and they echo private-school performance audits released by CSSC (2024). Policy implications include incentivising public–private partnerships to expand places and standardise quality assurance.

Rapid expansion of secondary enrolment following Tanzania’s 2015 fee-free policy has intensified debate over the comparative value of private education (UNESCO-IICBA, 2023). While case studies suggest private schools out-perform public peers (CSSC, 2024), systematic, nationwide evidence remains sparse. Leveraging the most recent NECTA dataset, this article asks:

Answering these questions provides empirically grounded insight for planners seeking to balance access with quality.

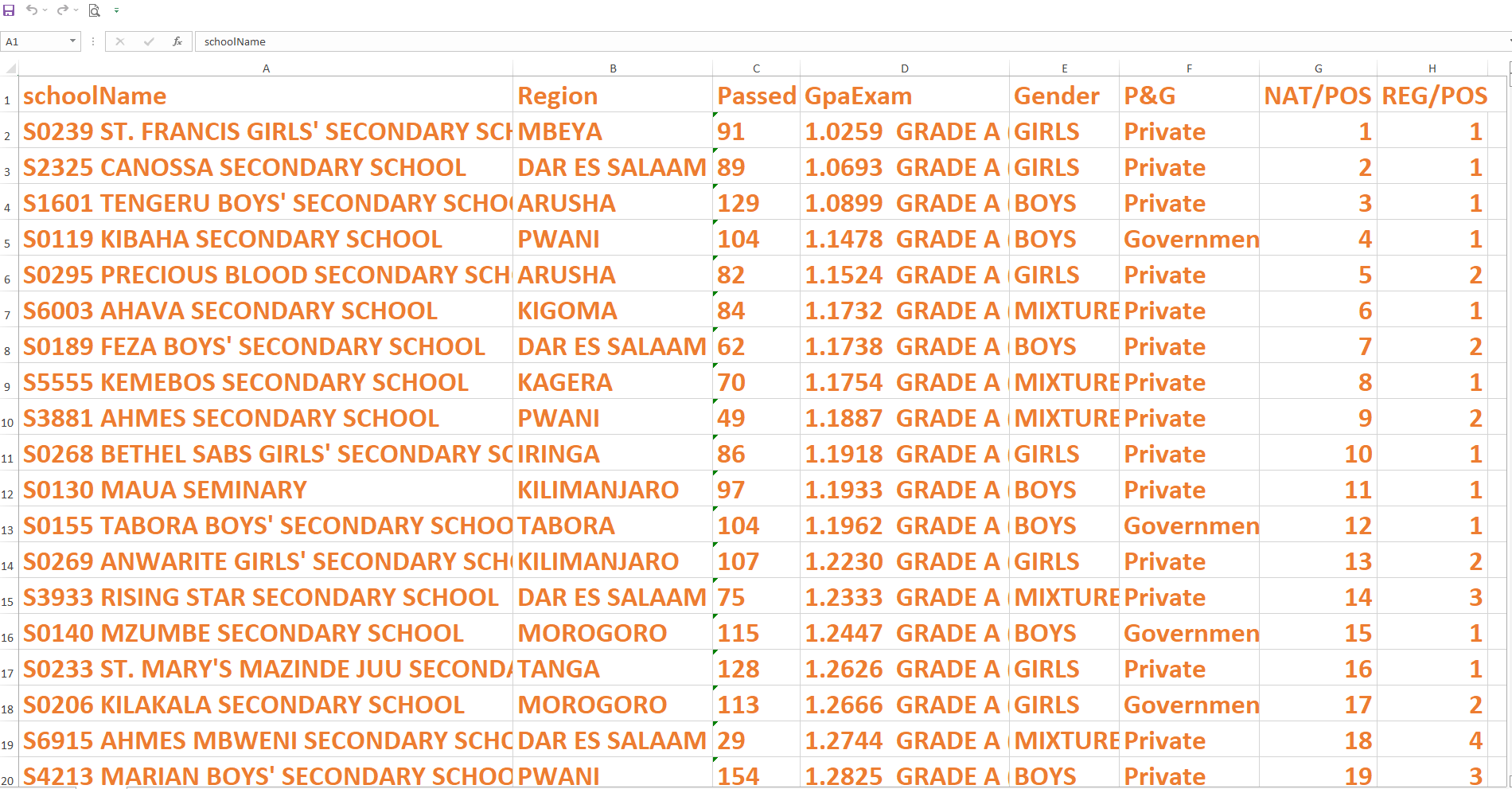

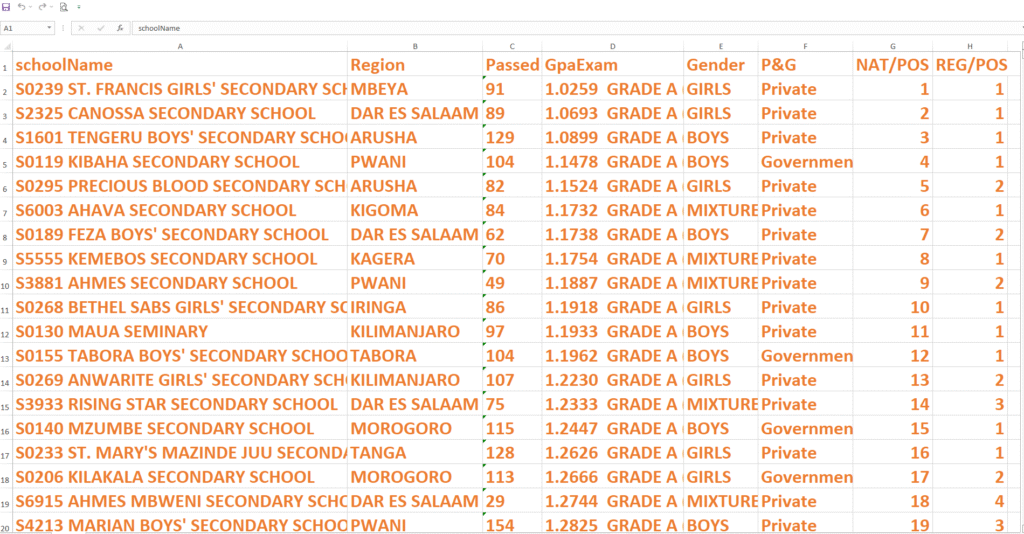

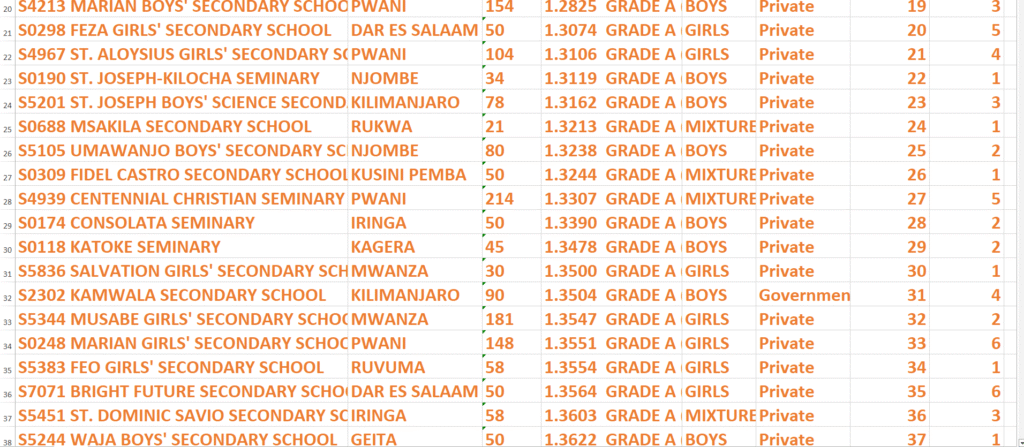

Dataset. An official Excel file MODIFIEDFORMFOURFINAL366VIDEO2024 containing centre-level CSEE 2024 results was ingested (N = 5 363). Key fields were centreGPA (converted to numeric), GPAGrade, Region, Gender mix and Ownership (Private/Government).

Cleaning & analysis. Non-numeric GPA entries were coerced to NaN (< 0.5 % of rows). Descriptive statistics, group means and proportional cross-tabs were computed in Python 3.11 (Pandas 2.2). Top-10 centres by GPA were extracted for illustration.

Limitations. Socio-economic controls (e.g., parental income) and school-level inputs (teacher–pupil ratio) were unavailable; hence causal inference is not attempted.

| Metric | Private (n = 2 287) | Government (n = 3 076) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean centre GPA | 3.01 | 3.82 |

| Grade A centres | 89 (5.13 %) | 8 (0.22 %) |

| Grade B centres | 519 (22.7 %) | 46 (1.5 %) |

Source: authors’ computation from NECTA 2024 file

The sizeable GPA gap corroborates qualitative accounts of overcrowding and resource dilution in government schools after fee-free expansion (ResearchGate, 2024). Private schools—often faith-based and boarding—maintain smaller class sizes and stricter academic cultures, translating into higher proportions of Division I–II passes (CSSC, 2024). Yet top government exemplars like Ilboru and Tallo demonstrate that public success is possible when leadership and infrastructure align (Mkapa & Mushi, 2024).

Three policy levers emerge:

Private secondary schools currently deliver a disproportionate share of Tanzania’s highest NECTA outcomes. While fee-free policy has boosted enrolment, quality gaps risk widening unless public capacity and accountability keep pace. Data-centred oversight and collaborative financing can help replicate high-performing models—public or private—nation-wide.

CSSC (2024) Form Four Schools Performance Report, Christian Social Services Commission, Dar es Salaam.

Lucumay, L. S. & Matete, R. E. (2024) ‘Challenges facing the implementation of fee-free education in primary schools in Tanzania’, International Journal of Education Policy, 12 (1), pp. 45–63.

NECTA (2025) CSEE 2024 Examination Results Enquiries, National Examinations Council of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam.

ResearchGate (2024) The implementation of the fee-free secondary education policy in Ukerewe district [online]. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/… (Accessed 25 June 2025).

SAGE Journals (2024) ‘Leading for quality: Reflection on school heads’ roles and tasks in community secondary schools in Tanzania’, Journal of School Leadership, 34 (2), pp. 175–192.

UNESCO-IICBA (2023) Teacher and Education Issues in Africa: Tanzania Country Factsheet, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Addis Ababa.

World Bank (2024) Tanzania Basic Education Public Expenditure Review, World Bank Group, Washington DC.

(All web links accessed 25 June 2025).

Sources